Mẫu là gì? Thiết kế là gì? Chúng ta vẫn đang nói về phát triển phần mềm phải không?

Chắc chắn là vậy.

As is the case with object-oriented programming, we, the developers, are trying to model the world surrounding us. As such, it makes sense to also try and use the world surrounding us as a tool to describe our craft.

In this case, we take a page from architecture (the one with buildings and bridges) and the seminal architecture book called A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, ConstructionbyChristopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein where patterns are described as follows:

Each pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice.

In software development, architecture is the process of constructing an application in a healthy, robust and maintainable way and patterns provide a way of giving names to solutions for common problems. These solutions can range from abstract/conceptual to very precise and technical and allow developers to effectively communicate with each other.

If two or more developers on a team are knowledgeable about patterns, talking about solutions to problems becomes very efficient. If only one developer knows about patterns, explaining them to the rest of the team is usually easy.

The goal of this article is to whet your appetite for a somewhat formal representation of knowledge in software development by introducing you to the idea of software design patterns and presenting a couple of patterns which are interesting because they get used considerably in modern JavaScript projects.

Singleton pattern

The what

The singleton pattern isn’t one of the most widely used ones, but we’re starting here because it’s relatively easy to grasp.

The singleton pattern stems from the mathematical concept of a singleton which is:

In mathematics, a singleton, also known as a unit set, is a set with exactly one element. For example, the set is a singleton.

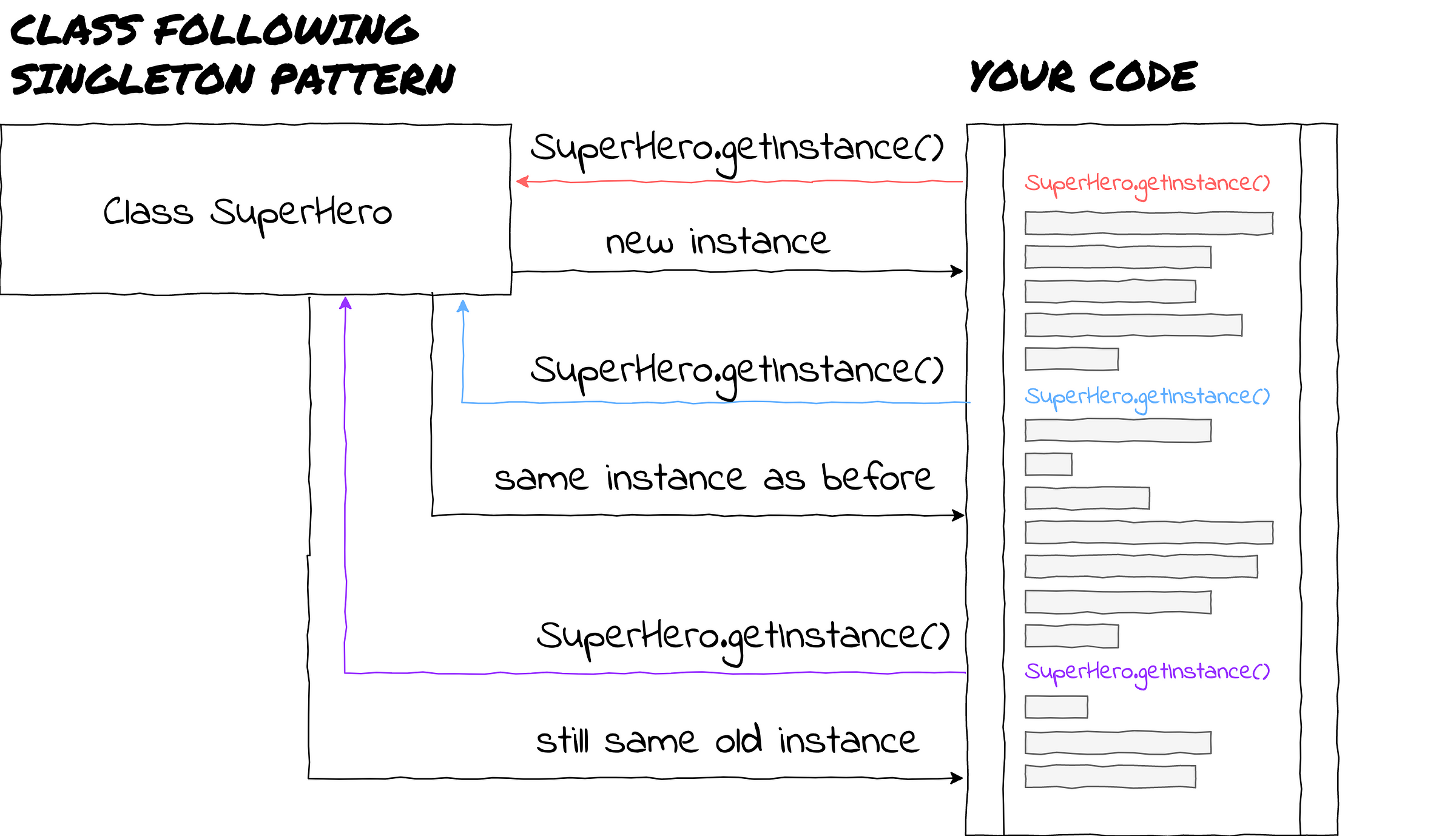

In software, it simply means that we limit the instantiation of a class to a single object. The first time an object of a class implementing the singleton pattern should be instantiated, it is actually going to get instantiated. Any subsequent try is just going to return that first instance.

The why

Apart from allowing us to only have one superhero ever (which would obviously be Batman), why would we ever use the singleton pattern?

Although the singleton pattern isn’t without its problems (it’s been called evil before with singletons being called pathological liars), it still has its uses. The most notable one would be for instantiating configuration objects. You probably only want one configuration instance for your application, unless a feature of your application is providing multiple configurations.

The where

Angular’s services are a prime example of the singleton pattern being used in a big popular framework. There is a dedicated page in Angular’s documentation explaining how to make sure that a service is always provided as a singleton.

Services being singletons makes a lot of sense, since services are used as a place to store state, configuration and allow communication between components and you want to make sure that there aren’t multiple instances messing up these concepts.

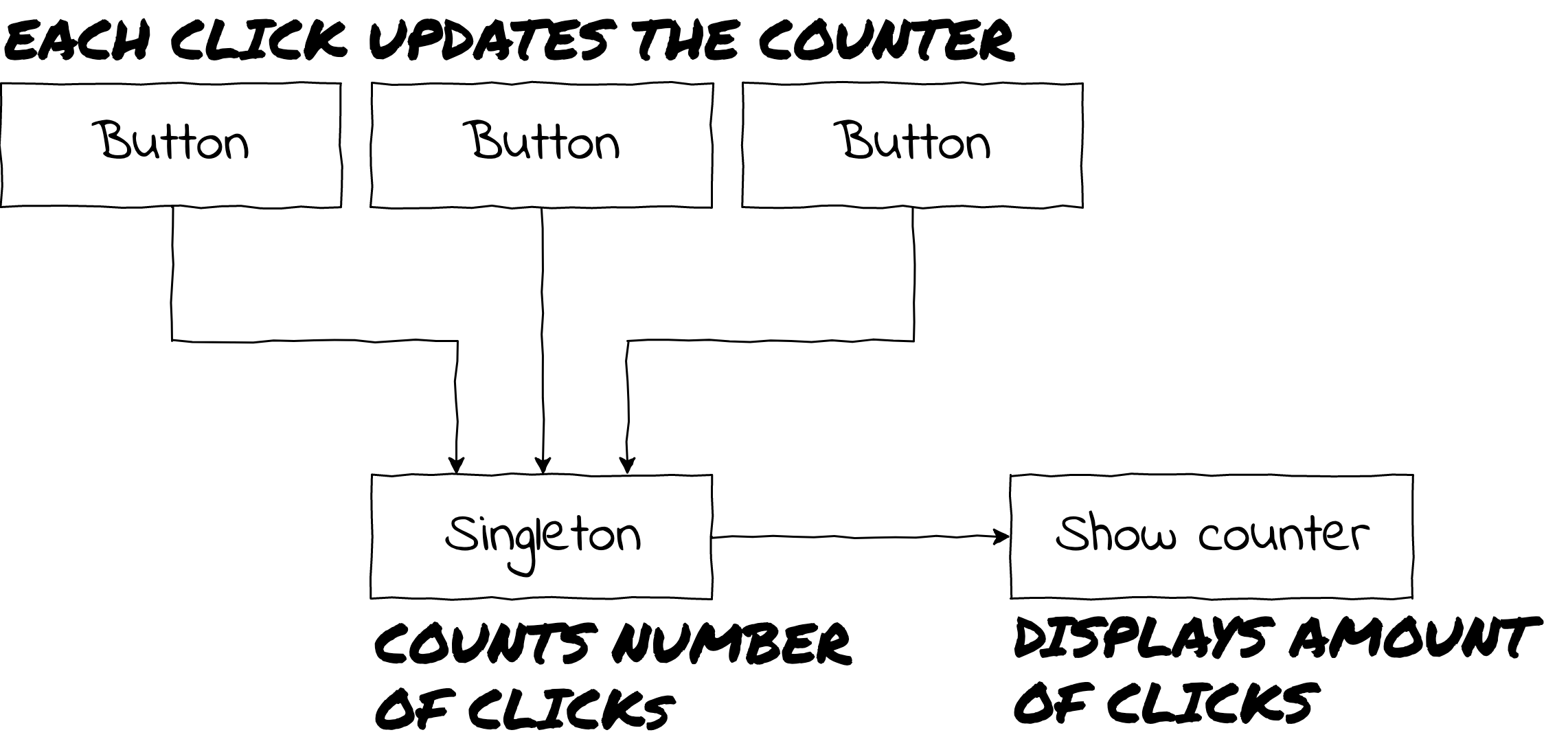

As an example, let’s say that you have a trivial application which is used for counting how many times buttons have been clicked.

You should keep track of the number of button presses in one object which provides:

- the functionality of counting

- and providing the current number of clicks.

If that object wasn’t a singleton (and the buttons would each get their own instance) the click count wouldn’t be correct. Also, which of the counting instances would you provide to the component showing the current count?

Observer pattern

The what

The observer pattern is defined as follows:

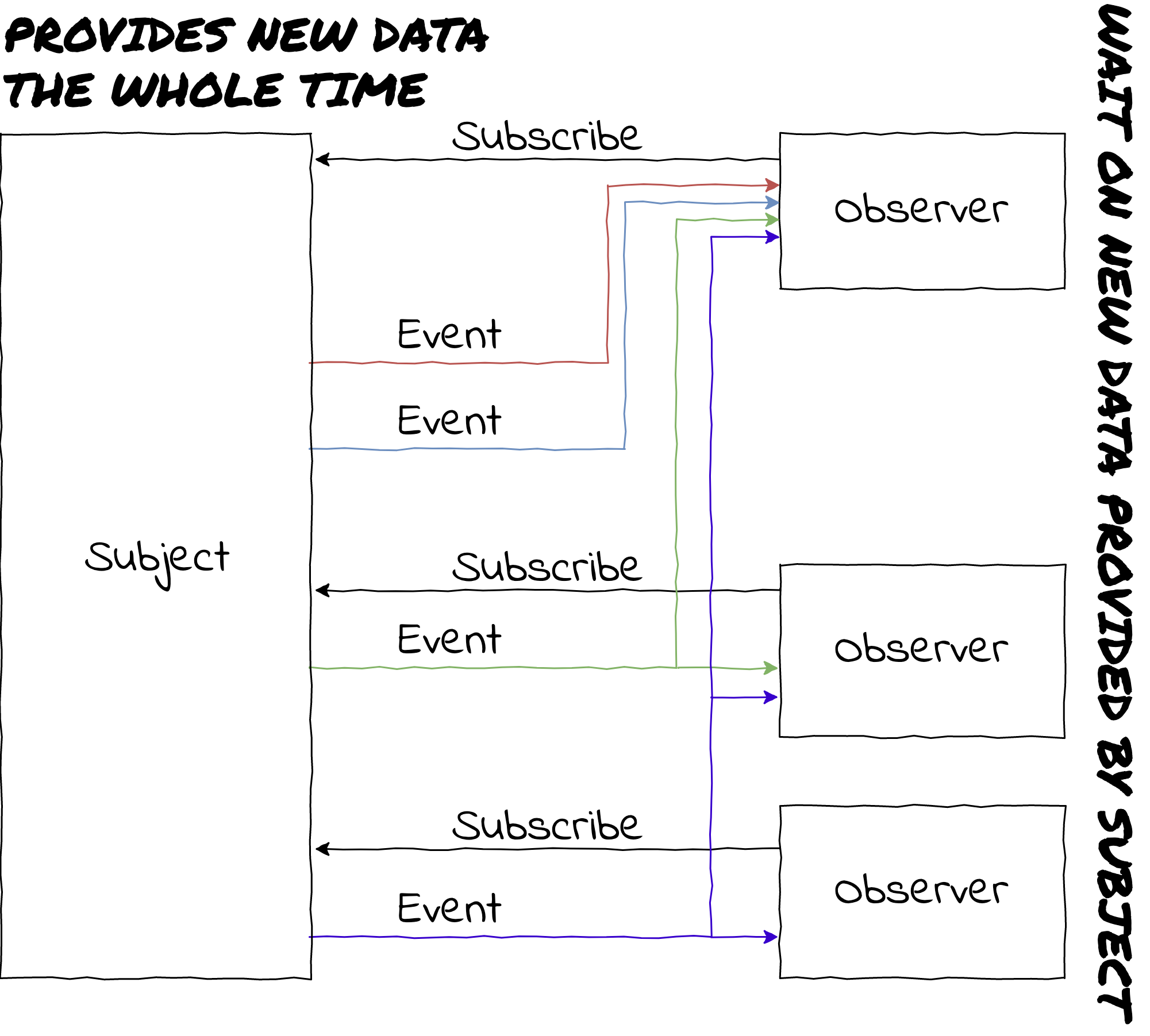

The observer pattern is a software design pattern in which an object, called the subject, maintains a list of its dependents, called observers, and notifies them automatically of any state changes, usually by calling one of their methods.

It’s really easy to understand the observer pattern if we try comparing it to an example in the real world — newspaper subscriptions.

The usual scenario when buying a newspaper is that you walk to the newsstand and ask if the new issue of your favourite newspaper is out. If it isn’t, it’s a sad affair of inefficiency where you have to walk home and try again later. In JavaScript terms, this would be the same as looping until you get the desired result. When you finally get your hands on the newspaper, you can do what you meant to do the whole time — sit down with a cup of coffee and enjoy your newspaper (or, in JavaScript terms, execute the callback function that you wanted to do the whole time).

The smart thing to do (and get your beloved newspaper each day) would be to subscribe to the newspaper. That way, the publishing company would let you know when a new issue of the newspaper is out and deliver it to you. No more running to the newsstand. No more disappointment. Bliss. In JavaScript terms, you wouldn’t be looping and asking for the result until you run a function any more. You would, instead, let a subject know that you are interested in events (messages) and would provide a callback function which should be called when new data is ready. You are, then, the observer.

The nice thing is — you don’t have to be the only subscriber. As you would be disappointed by missing your newspaper, so would other people, too. That’s why multiple observers can subscribe to the subject.

The why

The observer pattern has many use cases but generally, it should be used when you want to create a one-to-many dependency between objects which isn’t tightly coupled and have the possibility to let an open-ended number of objects know when a state has changed.

JavaScript is a great place for the observable pattern because everything is event-driven and, rather than always asking if an event happened, you should let the event inform you (like the old adage “Don’t call us we’ll call you”). Chances are you already did something which looks like the observer pattern — addEventListener. Adding an event listener to an element has all the markings of the observer pattern:

- you can subscribe to the object,

- you can unsubscribe from the object,

- and the object can broadcast an event to all its subscribers.

The big payoff from learning about the observer pattern is that you can implement your own subject or grasp an already existing solution much faster.

The where

Implementing a basic observable shouldn’t be too hard, but there is a great library being used by many projects and that’s ReactiveX of which RxJS is its JavaScript counterpart.

RxJS allows you not only to subscribe to subjects, but also gives you the possibility of transforming the data in any way you can imagine, combining multiple subscriptions, making asynchronous work more manageable and much much more. If you ever wanted to bring your data processing and transformation level to a higher level, RxJS would be a great library to learn.

Apart from the observer pattern, ReactiveX also prides itself with implementing the iterator pattern which gives subjects the possibility of letting its subscribers know when a subscription ended, effectively ending the subscription from the subject’s side. I am not going to be explaining the iterator pattern in this article, but it would be a great exercise for you to learn more about it and see how it fits in with the observable pattern.

Facade pattern

The what

The facade pattern is a pattern which takes its name from architecture. In architecture:

A facade is generally one exterior side of a building, usually the front. It is a foreign loan word from the French façade, which means “frontage” or “face”.

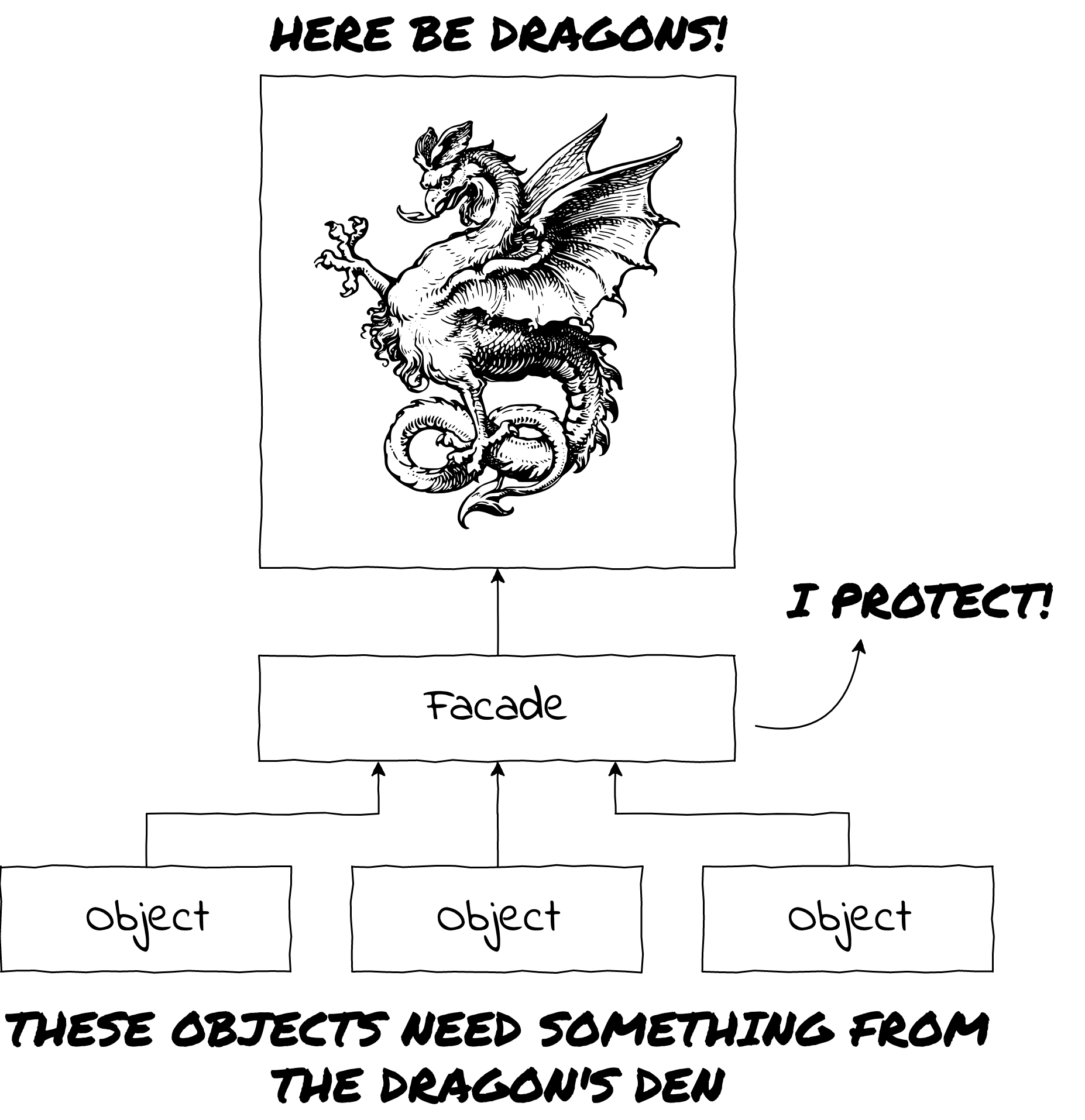

As the facade in architecture is an exterior of the building, hiding its inner workings, the facade pattern in software development tries to hide the underlying complexity behind a front, effectively allowing you to work with an API which is easier to grasp while providing the possibility to change the underlying code however you want.

The why

You can use the facade pattern in a myriad of situations but the most notable ones would be to make your code easier to understand (hide complexity) and to make dependencies as loosely coupled as possible.

It is easy to see why a facade object (or layer with multiple objects) would be a great thing. You don’t want to be dealing with dragons if it can be avoided. The facade object is going to provide you a nice API and deal with all the dragon shenanigans itself.

Another great thing that we can do here is change out the dragon from the background without ever touching the rest of the application. Let’s say that you want to change that dragon out with a kitten. It still has claws, but is much easier kept fed. Changing it out is a matter of rewriting the code in the facade without changing any of the dependent objects.

The where

A place where you will see facades often is Angular using its services as a means of simplifying background logic. But it doesn’t have to only be Angular, as you will see in the next example.

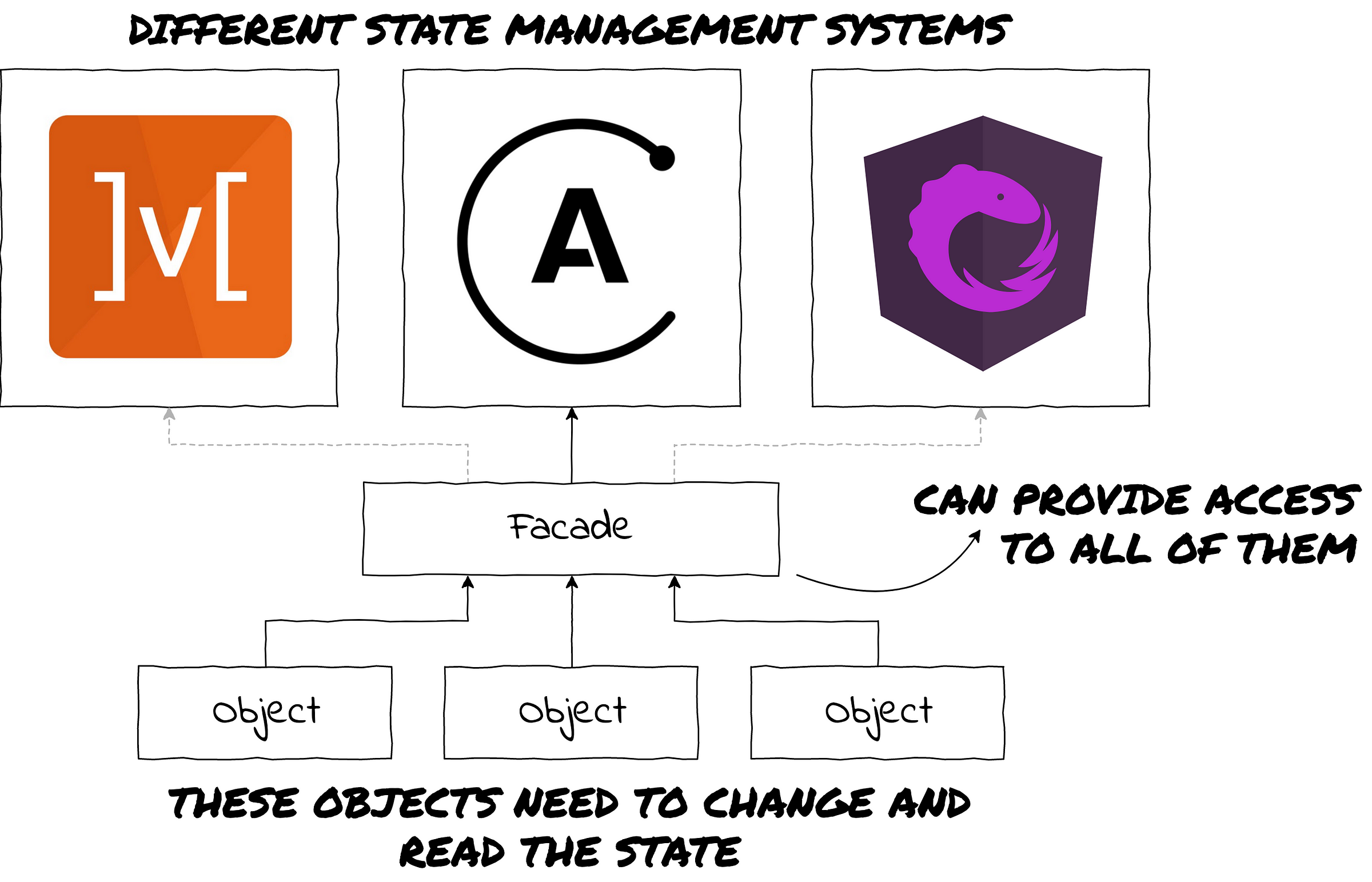

Let’s say that you want to add state management to your application. You could take Redux, NgRx, Akita, MobX, Apollo or any of the new kids on the block that have been popping up left and right. Well, why not choose them all and take them for a spin?

What are the basic functionalities a state management library is going to provide you?

Probably:

- a way of letting the state management know that you want a state change

- and a way of getting the current (slice of) state.

That doesn’t sound too bad.

Now, with the power of the facade pattern under your belt, you can write facades for each part of the state which are going to provide a nice API for you to work with — something like facade.startSpinner(), facade.stopSpinner() and facade.getSpinnerState(). These methods are really easy to understand and reason about.

After that, you can tackle the facade and write the code which is going to transform your code so that it works with Apollo (managing state with GraphQL — so hot right now). You may notice that it doesn’t suit your coding style at all or that the way unit tests have to be written really isn’t your cup of tea. No problem, write a new facade which is going to support MobX.

Where to go from here

You’ve probably noticed that there was no code or implementation of the design patterns I’ve talked about. That’s because each of these design patterns could be at least a chapter in a book for itself.

Now that we’re talking about books, it wouldn’t hurt to take a look at one or two dealing with design patterns in depth.

The first and biggest recommendation has to be Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Softwareby Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlisside also known as the Gang of Four. The book is a gold mine and the de facto bible of software design patterns.

If you are looking for something that’s a bit easier to digest, there is Head First Design Patterns by Bert Bates, Kathy Sierra, Eric Freeman and Elisabeth Robson. It’s a very nice book which tries to convey the message of design patterns through a visual perspective.

Last but not least, nothing beats just Googling, reading and trying out different approaches. Even if you end up never using a pattern or technique, you’ll learn something and grow in ways you never expected.